Is past prologue? Yes and no, when it comes to depressions.

Two certainties during any economic depression are high unemployment and high underemployment (workers in jobs for which they are overqualified). Unemployment peaked at 25 percent during the Great Depression.

These days, if unemployment climbs, its effect will be softer than it was during the Great Depression. Wealth redistribution mechanisms are now in place to reduce poverty. Further, more American households have two members in the workforce compared with the 1930s, in which the sole breadwinner was typically the male member of the household.

But high unemployment can have other effects.

Crime

Jean Valjean legendarily stole a loaf of bread for his family during an economic depression. Some aspects of society have not changed in 200 years. Unemployment and underemployment are often cited as causes for increases in crime rates. In a study of national crime rates between 1979 and 1997, university researchers concluded much of the increase in crime during that period could be explained by falling wages and rising unemployment among men without college educations.

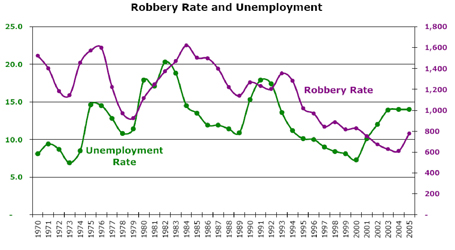

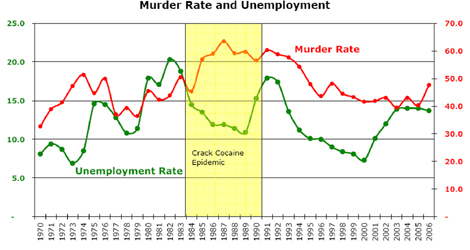

Detroit serves as a prime example. The charts show the high correlation of the unemployment rate with the murder and robbery rates in Detroit since 1970.

Source: David Martin, Ph.D. ,Wayne State University Center for Urban Studies.

http://www.cus.wayne.edu/content/presentations/Detroit_Crime%20Barometer_May_2007.pdf

Depopulation

Exodus from a failing region is common in an economic depression, exacerbating an area’s problems. The Great Depression saw the Okies head west to California. In recent years as jobs have left Detroit, so have one-third of its residents. In 1970, Detroit’s population was 1.5 million. Today, it is less than 1 million.

As populations migrate from job-poor areas, unskilled jobs often are filled by overqualified candidates. Foreign laborers who dominate certain industries such as landscaping and agriculture easily can be replaced by American workers. This would potentially reduce unemployment, but would certainly lead to underemployment of many Americans.

A depressed economy would also affect certain highly skilled jobs. For decades, the United States has attracted the world’s best and brightest. If the day comes when China and India offer more economic opportunity than the United States, highly talented Chinese and Indians may choose to stay closer to home.

According to a recent Kauffman Foundation study, 25 percent of U.S. science and technology companies founded between 1995 and 2005 were led by foreign-born executives or technologists. Fewer highly skilled immigrants (accompanied by an expected reduction in investment) would mean less technological innovation. The rate of productivity change in our lives would decline.

Household Destruction

On average, the United States creates 1.4 million new households per year. Generally, this happens when a recent college graduate moves out of her parents’ home, when immigrants come to America and when couples divorce. New households have an enormous effect on the economy beyond the dwellings in which they are created. Householders purchase mattresses and televisions, and use utilities. In a depression, the United States runs the risk of negative household formation, or household destruction. As mentioned above, in a high unemployment scenario, fewer immigrants would arrive. Recent college graduates would remain in their parents’ homes. Demand for housing would decrease. The timing could not be worse, as currently the American housing supply far exceeds demand. Real estate prices might drop further than forecast.

Japan has experience with reduced household formation. After its financial collapse (caused by inflated real estate prices) in 1990, Japan experienced what many call its “Lost Decade.” Annual GDP growth averaged less than 1 percent. Adult children moved in with their parents. These children, pejoratively referred to as “parasite singles,” continue to live with their parents well into their 30s.

The rising cost of housing has contributed to the number of such singles. Living with one’s parents permits young Japanese to devote more resources to other endeavors, such as entertainment. According to the Statistics Bureau of Japan, in 1980, 20.4 percent of Japanese aged 20-39 lived at home. By 2000, the number had grown to 34.1 percent. Older Japanese children were particularly represented, with 20.6 percent aged 30-34 living at home in 2000, compared with 7.6 percent 20 years prior. One can reasonably conclude that a stronger economy might have resulted in fewer young people living at home.

Medical Problems

Consumer spending today differs in some categories from the Depression era. On average, household budgets devote less to food and clothing and far more to medical care. See chart.

| Personal Consumption Expenditure | ||

| 1930 | 2007 | |

| Food | 25.7% | 13.7% |

| Clothing and Shoes | 11.4% | 3.9% |

| Medical Care | 3.4% | 17.3% |

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis | ||

Worldwide trade, stifled during the Great Depression, has reduced the prices of many imported goods such as produce and clothing. As long as international trade continues, bread lines will not be common in a 21st-century depression, but lines at the emergency room might be. Currently, 46 million Americans are uninsured. That number would rise in a depression as a result of job losses and corporate cutbacks. Government aid currently available to the uninsured would likely be reduced as budgets suffer. Preventive care would become a luxury as consumers avoided doctors’ visits to save money. Illnesses that could have been prevented or treated and cured would be left untreated and become more severe. Eventually, patients would be forced seek urgent care. The urgent care system would be overwhelmed. What was once a three-hour wait to set a broken arm could become a 10-hour ordeal.

A minimal level of health care should not be considered a luxury in any developed economy, but a depression might change that. Imagine if routine vaccinations became a discretionary purchase. Diseases previously considered to have been eliminated, such as measles, mumps, rubella and polio, might reemerge in American society.

A 21st-century depression would not create a hungry populace, but misery would rise. Everyone who was previously wealthy, middle class or working class would experience harsher conditions. Crime would increase and innovation would suffer. Fewer new households would form, but families might spend more time together — perhaps better for society though certainly not for the economy. Mortality might rise as medical care becomes unaffordable. It would be dreadful to recall for children and grandchildren when our society peaked. Let’s hope we are not in that position in the future.