1933 — President Roosevelt signs the Banking Act of 1933, or the Glass-Steagall Act, into law with the aim of restoring confidence in the banking system, which is at record lows after one in five banks failed following the 1929 stock market crash. The legislation separates commercial banks from investment banks to ensure that deposits are not subject to the risks associated with the underwriting and speculative trading of stocks and bonds that occurs within investment banks. The act puts Regulation Q into effect, setting interest rate ceilings on savings accounts and limiting competition among banks. The law also establishes the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to provide depositors an explicit guarantee and prevent bank runs. The federal government receives the right to regulate commercial bank operations.

1938 — The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) is established as a federal agency to increase home ownership and ensure a reliable supply of mortgage credit throughout the country. The primary function of Fannie Mae is to purchase, hold or sell Federal Housing Administration-insured mortgage loans originated by private lenders.

1968 — The 1968 Charter Act splits the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae) from Fannie Mae and transforms Fannie Mae into a “government-sponsored private corporation” to be shareholder owned and managed. The act also provides the authority to issue mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

1970 — The pendulum begins to swing toward less regulation as Glass-Steagall is weakened. The Bank Holding Company Act Amendments allows the development of new bank-like businesses that accept deposits or make commercial loans, but not both. The Emergency Home Finance Act of 1970 creates the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac) to compete with Fannie Mae with the intent of increasing liquidity, stability and affordability in the housing market.

1977 — The Community Reinvestment Act is passed to encourage depository institutions to help meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods.

1980 — The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act passes, phasing out Regulation Q caps on savings account interest rates. The removal of the limits increases competition among banks for deposits and narrows profits. This encourages banks to seek more profitable activities outside traditional deposit taking and lending.

1982 — Responding to lobbying and a volatile interest rate environment, Congress passes the Alternative Mortgage Transaction Parity Act of 1982 to increase the supply of credit available for home purchases. The bill specifically authorizes adjustable-rate mortgages and has provisions that allow for balloon payments and negative amortization, in which loan payments are so low that the outstanding balance increases over time.

1987 — The Federal Reserve Board eases restrictions imposed under the Glass-Steagall Act. The chairman of the Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker, expresses concern that lenders will lower loan standards in pursuit of lucrative securities offerings and will market bad loans to the public. The first collateralized debt obligation (CDO) is created by bankers at Drexel Burnham Lambert, employer of prominent American financier and “junk-bond king” Michael Milken, further expanding the credit supply. CDOs bundle myriad debt and carve it into segments of varying risk/return levels, or tranches. They are designed to spread risk among a large number of investors. By transferring their loans to investors, lenders are able to focus on the more profitable task of creating new loans.

1992 — The Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight is created to ensure that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are adequately capitalized and operating safely. The department imposes goals for increased financing of affordable housing in central cities as well as rural and other underserved areas.

1999 — The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act is signed, repealing part of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 and opening up competition among banks, securities companies and insurance companies. The act allows commercial and investment banks to consolidate.

2000 — President Clinton signs the Commodity Futures Modernization Act, giving the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) shared oversight of single stock futures. Other sections of the act carve out a separate group of derivatives and exempt them from regulation under either authority. The most prominent of the unregulated derivatives is credit default swaps (CDS), essentially insurance policies covering losses on securities in the event of default. The act allows hedge funds, investment banks and insurance companies to trade CDS with minimal supervision. Neither regulatory body has the authority to guarantee that the institutions have the assets to cover the losses they are guaranteeing.

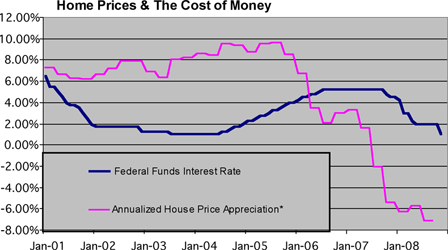

2001-2004 — In response to the bursting of the dot-com bubble in late 2000, the Federal Reserve brings the federal funds rate from 6.5 percent in January 2001 to 3.5 percent in August of that year. The easing policy continues after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, and interest rates reach 1.75 percent by the end of the year. Interest rate declines continue all the way to 1 percent in June 2003, and rates stay below 2 percent for the majority of 2004. For 31 consecutive months, the base inflation-adjusted short-term interest rate is negative. Banks are living in a world of virtually free money, and therefore have strong incentive to keep lending.

2004 — The SEC suspends the “net capital rule” for investment firms with more than $5 billion in assets. The ruling allows these companies to use mathematical models to calculate net capital requirements for market and derivatives-related credit risk. The changes are made with the assumption that the firms would effectively self-regulate and avoid undue risk-taking. Under the new rules, Bear Stearns is able to increase its leverage to $32.80 debt for $1 of equity from $26.40 for $1 in 2003, indicating a $179 billion increase in debt over four years.

2004 — More Americans than ever buy homes, and the U.S. homeownership rate peaks at an all-time high of 69.2 percent. Banks, underwriters and other lenders de-emphasize previous loan standards such as employment history, income, credit rating, assets and property loan-to-value ratios. Instead, they focus on the ability to securitize the mortgages, which is being supported by the demand for mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The mortgage denial rate for conventional home purchase loans plummeted from 29 percent in 1997 to about half that in 2002.

*Annualized appreciation based on the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s Seasonally-Adjusted House Price Index

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Federal Housing Finance Agency

2002-2007 — The credit rating agencies require various credit enhancements, but give AAA ratings to many subprime MBS. About 80 percent of mortgage-backed bonds are designated senior tranche (receive first repayments) and rated AAA, with the remaining tranches rated A, BBB and below. Conflicts of interest abound because MBS issuers not only pay the agencies for ratings, but also are free to shop around for the highest rating. The conflicts of interest are intensified by rating fees that are twice as high as those for corporate bonds. No natural market exists for lower-rated MBS, so these tranches are repackaged into CDOs with other collateralized loans such as car loans. Again, credit enhancements are used to make a large portion of the securities AAA rated. The lower-rated tranches are reworked into new CDOs, and the process pyramids. Total revenues for the three largest credit rating agencies double from $3 billion to $6 billion between 2002 and 2007. Moody’s has the highest profit margin of any company in the S&P 500 for five years in a row.

2005-2006 — According to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA), U.S. dollar-denominated CDO issuance more than doubles, from $209 billion in 2005 to $421 billion in 2006. Low interest rates that persisted for several years resulted in low returns on short-term risk-free securities. Eager for a higher rate of return, institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies, who generally seek long-term returns in the 5-6 percent range, move into MBSs and derivatives. The CDOs backed by mortgages are a popular choice, because the increased yield can be achieved at “low-risk” AAA rating.

2006 — Wachovia expands by acquiring Golden West Financial, a California mortgage lender focused on adjustable-rate mortgages and its signature “Pick-A-Payment” loans. Wachovia pays $24 billion, which is a 15 percent premium over Golden West’s market value at the time of the sale.

2007 — The Bank for International Settlements estimates that $57.9 trillion worth of assets are covered by credit-default swap contracts at the end of 2007, up from $20.3 trillion in June 2006, and several times the size of the entire U.S. stock market. Investment banks and insurance companies freed from regulation by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act continue to sell protection against defaults in a wide array of underlying assets, and are paid handsomely. Financial institutions and individuals investing in CDOs purchase credit-default swaps to protect themselves against CDO losses, adding more fuel to CDO demand and leading to even more mortgage lending. Counterparty risk builds because, as with any insurance contract, the default payout is only guaranteed if the insurer is solvent.

The Collapse

2007

February — More than 25 subprime lenders declare bankruptcy, announce significant losses or put themselves up for sale.

April — New Century Financial, the largest U.S. subprime lender, files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

June — Moody’s credit rating agency cuts the ratings of 131 securities backed by subprime mortgages and announces it is reviewing the grades of 136 others.

October — The S&P 500 stock market index hits its all-time high of 1,565.15 on October 9.

November — The Financial Accounting Standards Board’s rule regarding mark-to-market accounting takes effect, requiring companies to value derivatives and other financial instruments at the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants.

2008

January — The number of homes facing foreclosure is up 57 percent compared with the same month of the previous year. U.S. unemployment begins a sharp year-long rise. Citigroup reports a $9.8 billion loss for the fourth quarter and writes down $18 billion in subprime losses. The Fed makes its biggest rate cut in 25 years, 1.25 percentage points, to 3 percent.

March 16 — To avoid bankruptcy, Bear Stearns agrees to be taken over by JPMorgan Chase. The country begins to hear that certain companies are too big to fail.

July 11 — A bank run forces the FDIC to take control of IndyMac Bank, which had held $32 billion in assets in March. Depositors withdrew $1.3 billion after Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y., questioned the bank’s viability. Through November, 21 other banks failed during 2008.

September 7 — Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are taken over by the government and placed into conservatorship.

September 14 — Merrill Lynch agrees to sell itself to Bank of America to ensure its viability through the market turmoil. Lehman Brothers fails to find a purchaser and is forced to file for bankruptcy.

September 16 — In the face of $40 billion of redemptions in two days, the Reserve Primary Fund money market fund “breaks the buck,” falling to 97 cents after investors became concerned about the fund’s $785 million position in Lehman Brothers’ commercial paper. AIG receives an $85 billion loan from Federal Reserve Bank of New York in exchange for an almost 80 percent stake in the company. The actions are taken after rating agencies downgraded AIG’s credit rating, which would have caused the company to sell its assets in a fire sale to meet new collateral requirements.

September 21 — Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley announce that they will transform themselves into bank holding companies.

September 25 — After its credit rating downgrades triggered a run on the bank, Washington Mutual is seized by the FDIC, and its banking assets are sold to JPMorgan Chase. With $310 billion of assets, WaMu is the biggest bank failure in American history.

October 3 — The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 is passed and establishes the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP).

October 12 — The Federal Reserve approves Wells Fargo’s acquisition of Wachovia, which faced growing troubles associated with its 2006 acquisition of Golden West.

November 20 — The S&P 500 closes at 752.44, its lowest level since 1996, declining 51.9 percent from its October 2007 high.

November 23 — The government helps stabilize Citigroup after its share price is hammered, agreeing to provide $306 billion in loans and invest about $20 billion.

November 25 - The Fed announces that it will buy up to $100 billion of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and Federal Home Loan Banks debt on the open market. It also plans to purchase $500 billion in mortgage-backed securities and lend up to $200 billion to investors who offer credit card, auto or student loans to consumers.