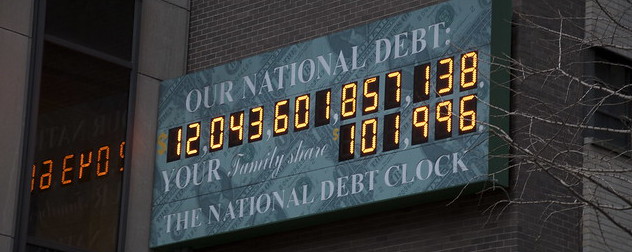

The National Debt Clock, New York City, in December 2009. Photo by Nick Webb.

The National Debt Clock, New York City, in December 2009. Photo by Nick Webb.If you follow the news, it may sometimes seem as if politicians on both sides of the aisle have opinions on every possible topic and are ready to express those opinions at length whenever they can. But one topic makes everyone quiet on Capitol Hill: debts and deficits.

As Gerald Seib observed in a Wall Street Journal column in February, President Trump didn’t mention the federal budget deficit in this year’s State of the Union address, nor did Democrat Stacey Abrams in her response. Nor is this silence out of sync with the rest of Washington; mentions of both the deficit and the national debt have dropped fairly steadily since 2011. As Seib wrote, “All told, Washington’s red-ink alarms have gone dead, even though the annual deficit will reach roughly $900 billion this year, then pass the trillion-dollar mark annually starting in 2022.”

Politicians have not abandoned talk about the deficit because voters don’t care. A Pew Research Center report from October 2018 found that 61 percent of Republican voters and 56 percent of Democratic voters believed the federal budget deficit is a “very big” problem. The numbers back them up. The federal debt hit a new high of $22 trillion in February and represented 78 percent of gross domestic product by the end of 2018.

Even so, politicians seem to feel, as a group, that this is a subject better left alone. After all, a candidate who runs on a platform of “Let’s raise taxes, but we won’t create any new programs or benefits, we’ll just pay down debt” is unlikely to win any elections in the current economic and political climate. Instead, by and large, Republicans hope that a growing economy will erase the problem. Many Democrats, meanwhile, have begun to question the extent to which deficits are a problem in the first place. Former Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Jason Furman and ex-Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, both Democrats, made this argument in a recent essay for Foreign Affairs magazine; the theory goes that government investments in education, health care and infrastructure will all help the economy more than entitlement cuts aimed at deficit reduction would. Advocates of “modern monetary theory” go even further, championing a view that has been widely interpreted as arguing that governments borrowing in their own currencies should not worry about budget constraints because they can print money to pay their bills.

Right now we are doing practically nothing to address our deficit problem. America has lived with big federal deficits for years without short-term consequences, which has led some to ignore the economic harm involved. Yet such harm is bound to arrive eventually. As Martin Feldstein, a professor at Harvard and the former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, observed in a Wall Street Journal opinion column recently, a higher debt-to-GDP ratio would eventually slow down the economy and crowd out business investment. When the economy slows enough, and when interest rates inevitably rise, the cycle could become self-perpetuating. Even Furman and Summers, who argued that focusing too much on deficit reduction is counterproductive, warned that ignoring rising federal debt levels outright is unwise. Policymakers need to act, and soon, regardless of whether doing so is popular.

As for what, specifically, lawmakers should do, the answer to any problem this big is bound to be complicated. That said, taking a first step is better than doing nothing at all. An obvious candidate for that step is to raise the retirement age for Social Security.

I am the father of two young children, and someone recently commented to me that my kids could live to be 120. This gave me a jolt, but the idea isn’t without basis. My colleague Ben Sullivan wrote about the challenges of longer life for retirement planning back in 2013, and he noted then that the first person who would live to 150 has likely already been born. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a dip in life expectancy in 2018, this is largely a result of the opioid epidemic; the life expectancy for Americans who reach age 65 rose slightly last year, in line with a long-standing trend. Without underplaying the seriousness of the opioid crisis, it does not seem unreasonable to assume that many Americans can expect to live longer in the decades to come. If the retirement age for full Social Security benefits stays fixed at 67 years old, eventually people could live 55 or 60 years past that age. The economics simply will not work.

Arguably, the economics are not working now. As I wrote in this space last summer, Social Security’s trustees have been ringing the funding alarm for the past few years, noting in their most recent annual report that the program’s trust fund will be depleted by 2034 if lawmakers don’t enact major changes in the interim. The program’s funding troubles are, in part, a simple function of demographics: Americans are living longer and having fewer children. As a result, there are fewer workers paying into the program relative to beneficiaries expecting payments.

Raising the Social Security retirement age would demonstrate seriousness about the deficit problem. If done intelligently, it also should not bear an outrageous political cost for lawmakers. Congress almost certainly would not enforce the new age threshold instantly. As they did in 1983, the last time they raised the age of eligibility for full benefits, lawmakers likely would phase in the new rules based on participants’ date of birth, ensuring that the people affected had plenty of time left to save for a later retirement date. At the time Congress raised Social Security retirement age to 67, the average life expectancy was 74.6 at birth and 16.7 at age 65; today, those figures are 78.6 and 19.4, respectively. Under the circumstances, raising eligibility for full benefits to age 70 or 71 would more or less stay in line with this shift. And indexing retirement age to life expectancy would mean not having to revisit this issue over and over again in the future.

While I can’t speak for an entire generation, I believe young people are more worried about other parts of the social safety net than they are about government-funded retirement. Congress should be mindful of the funding for Medicaid, Medicare and federal disability insurance, for instance, to be sure that Americans who genuinely cannot work because of health problems – at any age – have some level of support. Unfortunately, all of these programs are also contributing to the federal debt problem, but we are not fixing everything at once in this example. In relative terms, it makes sense to hit the brakes on Social Security retirement benefits first.

Many young adults also report that they are not sure whether they will be able to retire at all, at least in the sense their parents did, and that if they do, they do not expect Social Security to make up a significant part of their nest egg. A Transamerica survey of Americans between the ages of 18 and 39 found that 81 percent believed that Social Security as we know it won’t be around by the time they retire. For voters who believe this, pushing back the retirement age is likely to be a nonfactor.

Today’s 20- and 30-somethings have many places to focus their political outrage. I simply don’t see them refusing to vote for politicians in large numbers over a relatively moderate entitlement change of this nature. Meanwhile, raising the Social Security retirement age could do a great deal to keep the program solvent and help reduce the overall deficit. It will not solve the problem alone, but it would serve as a significant step toward doing so.

First, however, policymakers must break their silence on the deficit. Until real dialogue on the subject is possible, real action remains out of reach.

Posted by Paul Jacobs, CFP®, EA

The National Debt Clock, New York City, in December 2009. Photo by Nick Webb.

If you follow the news, it may sometimes seem as if politicians on both sides of the aisle have opinions on every possible topic and are ready to express those opinions at length whenever they can. But one topic makes everyone quiet on Capitol Hill: debts and deficits.

As Gerald Seib observed in a Wall Street Journal column in February, President Trump didn’t mention the federal budget deficit in this year’s State of the Union address, nor did Democrat Stacey Abrams in her response. Nor is this silence out of sync with the rest of Washington; mentions of both the deficit and the national debt have dropped fairly steadily since 2011. As Seib wrote, “All told, Washington’s red-ink alarms have gone dead, even though the annual deficit will reach roughly $900 billion this year, then pass the trillion-dollar mark annually starting in 2022.”

Politicians have not abandoned talk about the deficit because voters don’t care. A Pew Research Center report from October 2018 found that 61 percent of Republican voters and 56 percent of Democratic voters believed the federal budget deficit is a “very big” problem. The numbers back them up. The federal debt hit a new high of $22 trillion in February and represented 78 percent of gross domestic product by the end of 2018.

Even so, politicians seem to feel, as a group, that this is a subject better left alone. After all, a candidate who runs on a platform of “Let’s raise taxes, but we won’t create any new programs or benefits, we’ll just pay down debt” is unlikely to win any elections in the current economic and political climate. Instead, by and large, Republicans hope that a growing economy will erase the problem. Many Democrats, meanwhile, have begun to question the extent to which deficits are a problem in the first place. Former Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Jason Furman and ex-Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, both Democrats, made this argument in a recent essay for Foreign Affairs magazine; the theory goes that government investments in education, health care and infrastructure will all help the economy more than entitlement cuts aimed at deficit reduction would. Advocates of “modern monetary theory” go even further, championing a view that has been widely interpreted as arguing that governments borrowing in their own currencies should not worry about budget constraints because they can print money to pay their bills.

Right now we are doing practically nothing to address our deficit problem. America has lived with big federal deficits for years without short-term consequences, which has led some to ignore the economic harm involved. Yet such harm is bound to arrive eventually. As Martin Feldstein, a professor at Harvard and the former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, observed in a Wall Street Journal opinion column recently, a higher debt-to-GDP ratio would eventually slow down the economy and crowd out business investment. When the economy slows enough, and when interest rates inevitably rise, the cycle could become self-perpetuating. Even Furman and Summers, who argued that focusing too much on deficit reduction is counterproductive, warned that ignoring rising federal debt levels outright is unwise. Policymakers need to act, and soon, regardless of whether doing so is popular.

As for what, specifically, lawmakers should do, the answer to any problem this big is bound to be complicated. That said, taking a first step is better than doing nothing at all. An obvious candidate for that step is to raise the retirement age for Social Security.

I am the father of two young children, and someone recently commented to me that my kids could live to be 120. This gave me a jolt, but the idea isn’t without basis. My colleague Ben Sullivan wrote about the challenges of longer life for retirement planning back in 2013, and he noted then that the first person who would live to 150 has likely already been born. While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a dip in life expectancy in 2018, this is largely a result of the opioid epidemic; the life expectancy for Americans who reach age 65 rose slightly last year, in line with a long-standing trend. Without underplaying the seriousness of the opioid crisis, it does not seem unreasonable to assume that many Americans can expect to live longer in the decades to come. If the retirement age for full Social Security benefits stays fixed at 67 years old, eventually people could live 55 or 60 years past that age. The economics simply will not work.

Arguably, the economics are not working now. As I wrote in this space last summer, Social Security’s trustees have been ringing the funding alarm for the past few years, noting in their most recent annual report that the program’s trust fund will be depleted by 2034 if lawmakers don’t enact major changes in the interim. The program’s funding troubles are, in part, a simple function of demographics: Americans are living longer and having fewer children. As a result, there are fewer workers paying into the program relative to beneficiaries expecting payments.

Raising the Social Security retirement age would demonstrate seriousness about the deficit problem. If done intelligently, it also should not bear an outrageous political cost for lawmakers. Congress almost certainly would not enforce the new age threshold instantly. As they did in 1983, the last time they raised the age of eligibility for full benefits, lawmakers likely would phase in the new rules based on participants’ date of birth, ensuring that the people affected had plenty of time left to save for a later retirement date. At the time Congress raised Social Security retirement age to 67, the average life expectancy was 74.6 at birth and 16.7 at age 65; today, those figures are 78.6 and 19.4, respectively. Under the circumstances, raising eligibility for full benefits to age 70 or 71 would more or less stay in line with this shift. And indexing retirement age to life expectancy would mean not having to revisit this issue over and over again in the future.

While I can’t speak for an entire generation, I believe young people are more worried about other parts of the social safety net than they are about government-funded retirement. Congress should be mindful of the funding for Medicaid, Medicare and federal disability insurance, for instance, to be sure that Americans who genuinely cannot work because of health problems – at any age – have some level of support. Unfortunately, all of these programs are also contributing to the federal debt problem, but we are not fixing everything at once in this example. In relative terms, it makes sense to hit the brakes on Social Security retirement benefits first.

Many young adults also report that they are not sure whether they will be able to retire at all, at least in the sense their parents did, and that if they do, they do not expect Social Security to make up a significant part of their nest egg. A Transamerica survey of Americans between the ages of 18 and 39 found that 81 percent believed that Social Security as we know it won’t be around by the time they retire. For voters who believe this, pushing back the retirement age is likely to be a nonfactor.

Today’s 20- and 30-somethings have many places to focus their political outrage. I simply don’t see them refusing to vote for politicians in large numbers over a relatively moderate entitlement change of this nature. Meanwhile, raising the Social Security retirement age could do a great deal to keep the program solvent and help reduce the overall deficit. It will not solve the problem alone, but it would serve as a significant step toward doing so.

First, however, policymakers must break their silence on the deficit. Until real dialogue on the subject is possible, real action remains out of reach.

Related posts: