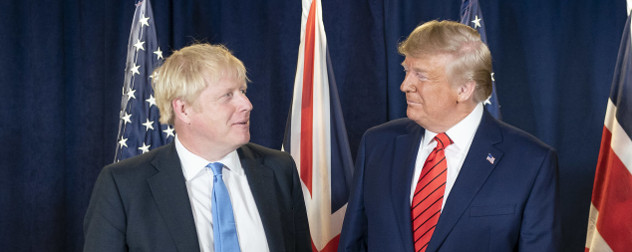

Boris Johnson and Donald Trump in September 2019. Photo by Shealah Craighead, courtesy The White House.

Boris Johnson and Donald Trump in September 2019. Photo by Shealah Craighead, courtesy The White House.China’s leaders have a contentious relationship with the truth, and while they have considerable latitude to twist reality to suit their tastes within their borders, the international community is becoming less willing to play along.

As China prepared to pass a security law that many activists see as the end of free expression and migration in Hong Kong, I observed in this space recently that other countries should encourage large-scale emigration from that city to take advantage of its population’s many talents. Now the United Kingdom is preparing to do just that. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said Wednesday, in a column for The Times of London, that the U.K. would “have no choice” but to offer an alternative to Hong Kong residents if China imposes the new security law. The prime minister argued that if the law goes into force as planned, China would be violating the Joint Declaration that supports the “one country, two systems” concept under which Hong Kong is meant to operate.

In that event, Johnson said the U.K. will change its immigration rules to offer a path to citizenship to nearly 3 million Hong Kong residents. Once the Chinese law is in force, people in Hong Kong who hold British National (Overseas) passports will be allowed to enter the U.K. for 12 months without a visa, up from the present six. Passport holders also would be eligible to renew that 12-month period and would secure the right to work. This could allow BNO passport holders to start the British citizenship process. The BBC reported that the U.K. is in talks with the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand about coordinating a further response to the security law.

A potential exodus of citizens from Hong Kong is not Beijing’s only incoming headache. The same day that Johnson announced potential changes to U.K. immigration law, President Donald Trump threatened to cut off Chinese airlines’ direct flights to the United States. China had, to that point, declined to approve U.S. carriers’ requests to resume direct flights to China after suspending them in response to the coronavirus pandemic. The U.S. Transportation Department said China’s refusal to grant requests from Delta Air Lines and United Airlines violated an agreement between the countries governing air travel.

The threat seemed to grab Beijing’s attention. Within 24 hours of Trump’s demand, China announced that American and other foreign airlines would be allowed to resume direct flights to the country. Such flights would be limited to a single flight on a single route per week by each carrier, which would match current service levels offered by the four Chinese airlines still flying directly to the United States. However, it is less than the two countries’ pre-pandemic treaty authorizes, and less than Delta and United Airlines want to provide, according to The Wall Street Journal. At this writing, the order blocking Chinese airlines’ U.S. flights was still slated to take effect June 16, subject to change by the president.

China has also recently clashed with Canada and Australia. As I noted in this space yesterday, a Canadian judge ruled late last month that the United States’ case to extradite Huawei’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, can proceed. Chinese-Canadian relations, already strained, are unlikely to improve as a result. And Australia has pushed back against China’s resistance to an inquiry into the source of the coronavirus pandemic. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Foreign Minister Marise Payne led calls for an international investigation, which was backed by a resolution that the World Health Organization’s governing body, the World Health Assembly, adopted last month. Australia has also joined Canada, the U.K. and the U.S. in condemning China’s new national security law.

The European Union, in contrast, has done what it does best: mostly talk, with little action behind it. EU leaders issued a statement of “grave concern” about China’s harsher stance toward Hong Kong. But they have also ruled out the possibility of sanctions or other economic consequences. In addition, Brussels remains committed to an EU-China summit in September, if the pandemic allows it to take place.

None of these actions, and certainly none of these declarations, is an insurmountable blow to China. But together, they signal that the international community won’t shrug off Chinese misbehavior forever, regardless of the country’s economic and presumed military strength. Actions have consequences. China is now getting a taste of what it is like when other countries treat it the way its behavior warrants, and it is evidently unpalatable.

In response to Johnson’s statement on Hong Kong immigration, China warned the U.K. to “step back from the brink” and “stop interfering,” Business Insider reported. Such threats are not hollow. Mere days after Meng’s arrest, Chinese authorities arrested a pair Canadians in a clear retaliatory measure. Both men are still being held with limited access to consular services. A third Canadian, who had earlier received a 15-month sentence for drug smuggling, now faces a death penalty. When cash and threats fail, China is not above taking hostages to achieve its goals.

Yet China’s diplomatic weapon of choice is clearly its pocketbook. Australia took an especially harsh blow when China announced an 80% tariff on its barley exports and banned a large proportion of its beef exports altogether. Over one-third of Australia’s exports go to China, including more than half of its barley. Kudos to Canberra for being willing to push back against Beijing on Hong Kong even after the economic damage it suffered as a result of calling for a coronavirus investigation.

Christopher Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, recently told the BBC, “I think we’re entering a period of realism with China.” Chinese leaders are not fond of realism. But they may have to learn to tolerate it if major trade partners that honor truth and democracy stand their ground.

Posted by Larry M. Elkin, CPA, CFP®

Boris Johnson and Donald Trump in September 2019. Photo by Shealah Craighead, courtesy The White House.

China’s leaders have a contentious relationship with the truth, and while they have considerable latitude to twist reality to suit their tastes within their borders, the international community is becoming less willing to play along.

As China prepared to pass a security law that many activists see as the end of free expression and migration in Hong Kong, I observed in this space recently that other countries should encourage large-scale emigration from that city to take advantage of its population’s many talents. Now the United Kingdom is preparing to do just that. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said Wednesday, in a column for The Times of London, that the U.K. would “have no choice” but to offer an alternative to Hong Kong residents if China imposes the new security law. The prime minister argued that if the law goes into force as planned, China would be violating the Joint Declaration that supports the “one country, two systems” concept under which Hong Kong is meant to operate.

In that event, Johnson said the U.K. will change its immigration rules to offer a path to citizenship to nearly 3 million Hong Kong residents. Once the Chinese law is in force, people in Hong Kong who hold British National (Overseas) passports will be allowed to enter the U.K. for 12 months without a visa, up from the present six. Passport holders also would be eligible to renew that 12-month period and would secure the right to work. This could allow BNO passport holders to start the British citizenship process. The BBC reported that the U.K. is in talks with the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand about coordinating a further response to the security law.

A potential exodus of citizens from Hong Kong is not Beijing’s only incoming headache. The same day that Johnson announced potential changes to U.K. immigration law, President Donald Trump threatened to cut off Chinese airlines’ direct flights to the United States. China had, to that point, declined to approve U.S. carriers’ requests to resume direct flights to China after suspending them in response to the coronavirus pandemic. The U.S. Transportation Department said China’s refusal to grant requests from Delta Air Lines and United Airlines violated an agreement between the countries governing air travel.

The threat seemed to grab Beijing’s attention. Within 24 hours of Trump’s demand, China announced that American and other foreign airlines would be allowed to resume direct flights to the country. Such flights would be limited to a single flight on a single route per week by each carrier, which would match current service levels offered by the four Chinese airlines still flying directly to the United States. However, it is less than the two countries’ pre-pandemic treaty authorizes, and less than Delta and United Airlines want to provide, according to The Wall Street Journal. At this writing, the order blocking Chinese airlines’ U.S. flights was still slated to take effect June 16, subject to change by the president.

China has also recently clashed with Canada and Australia. As I noted in this space yesterday, a Canadian judge ruled late last month that the United States’ case to extradite Huawei’s chief financial officer, Meng Wanzhou, can proceed. Chinese-Canadian relations, already strained, are unlikely to improve as a result. And Australia has pushed back against China’s resistance to an inquiry into the source of the coronavirus pandemic. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Foreign Minister Marise Payne led calls for an international investigation, which was backed by a resolution that the World Health Organization’s governing body, the World Health Assembly, adopted last month. Australia has also joined Canada, the U.K. and the U.S. in condemning China’s new national security law.

The European Union, in contrast, has done what it does best: mostly talk, with little action behind it. EU leaders issued a statement of “grave concern” about China’s harsher stance toward Hong Kong. But they have also ruled out the possibility of sanctions or other economic consequences. In addition, Brussels remains committed to an EU-China summit in September, if the pandemic allows it to take place.

None of these actions, and certainly none of these declarations, is an insurmountable blow to China. But together, they signal that the international community won’t shrug off Chinese misbehavior forever, regardless of the country’s economic and presumed military strength. Actions have consequences. China is now getting a taste of what it is like when other countries treat it the way its behavior warrants, and it is evidently unpalatable.

In response to Johnson’s statement on Hong Kong immigration, China warned the U.K. to “step back from the brink” and “stop interfering,” Business Insider reported. Such threats are not hollow. Mere days after Meng’s arrest, Chinese authorities arrested a pair Canadians in a clear retaliatory measure. Both men are still being held with limited access to consular services. A third Canadian, who had earlier received a 15-month sentence for drug smuggling, now faces a death penalty. When cash and threats fail, China is not above taking hostages to achieve its goals.

Yet China’s diplomatic weapon of choice is clearly its pocketbook. Australia took an especially harsh blow when China announced an 80% tariff on its barley exports and banned a large proportion of its beef exports altogether. Over one-third of Australia’s exports go to China, including more than half of its barley. Kudos to Canberra for being willing to push back against Beijing on Hong Kong even after the economic damage it suffered as a result of calling for a coronavirus investigation.

Christopher Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong, recently told the BBC, “I think we’re entering a period of realism with China.” Chinese leaders are not fond of realism. But they may have to learn to tolerate it if major trade partners that honor truth and democracy stand their ground.

Related posts: