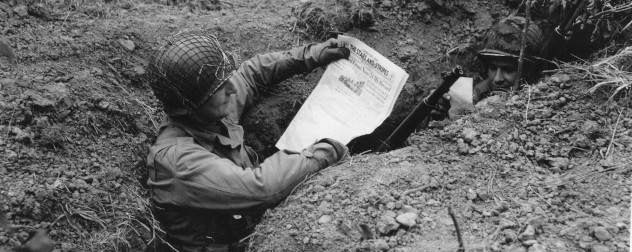

A GI reads the latest issue of Stars and Stripes, Sainte-Marguerite-d'Elle, France, June 16, 1944.

A GI reads the latest issue of Stars and Stripes, Sainte-Marguerite-d'Elle, France, June 16, 1944.

Photo by Wright, courtesy the U.S. National Archives/Signal Corps Archive.While news outlets everywhere struggle to survive, the one that retired Gen. David Petraeus once called “the hometown newspaper of the U.S. military” faces summary execution by budgetary guillotine.

Fortunately, President Donald Trump seems prepared to issue a last-minute pardon. Or maybe he already has, depending on how much legal force a tweet from the commander-in-chief carries inside the Pentagon.

For reasons that are obvious only to himself, Defense Secretary Mark Esper was intent on shutting down the Stars and Stripes, which has been part of American military life as far back as the Civil War. Many journalists who later became famous launched their careers at the paper. But it rose to national prominence during World War II largely through the work of one man: cartoonist Bill Mauldin.

Sgt. Mauldin told the story of the war through the eyes of Willie and Joe, two GIs who were not exactly in it for the glory. His nationally syndicated cartoon series, “Up Front,” offered a different view of the war than the one the wartime newsreels and feature films presented. Willie and Joe were bone-tired and war-weary, hoping to survive and go home, but not excited about their prospects. They did not encounter sinister SS storm troopers and Gestapo secret police in combat. Instead, the enemy they faced was made up of other grunts, much like themselves. Mauldin did not disparage the war’s cause, but he did not minimize its cost, either.

Gen. George S. Patton was not a fan. As Allied troops pushed eastward from France in the war’s final months, Patton summoned Mauldin to his palatial Luxembourg headquarters for a stern (and, as Mauldin later recalled, frequently profane) dressing down. But other than jawboning, the imperious general could do little to the young enlisted man. By statute then and now, Stars and Stripes operates with editorial independence, even though it receives financial support and crucial distribution and logistical services from the military.

Mauldin’s wartime work won him his first Pulitzer Prize in 1945, when he was 23. Long after the war, his sardonic cartoons offered baby boomers like me a glimpse of our fathers’ military experiences, which many of them preferred not to speak about.

Although most Americans outside the military community rarely encounter it, Stars and Stripes has continued to bring news of interest to service members through all the conflicts and deployments our military has faced to the present day, from Korea to Afghanistan and Iraq. Whether active-duty military or civilian, Stars and Stripes journalists go where the troops go. A 2019 documentary narrated by “60 Minutes” correspondent Steve Kroft – a Stars and Stripes alumnus – was titled “The World’s Most Dangerous Paper Route.”

Maybe Esper, a West Point graduate, was channeling his inner Patton when he sought to defund Stars and Stripes. The military is a command-and-control organization; it is surely grating at times to have a communications arm of the Pentagon that is, in most respects, independent of that chain of command. Considering the pittance that Stars and Stripes costs in the context of our military budget, the stated rationale of budgetary efficiency lacks credibility. The Pentagon’s contribution to the paper’s budget comes to less than $16 million a year. Esper told reporters that the cut would fund “higher-priority issues” in a military whose annual budget is almost $700 billion. A recent Pentagon memo ordering Stars and Stripes to cease publication after Sept. 30, the end of the current federal fiscal year, had the hallmarks of someone grinding an ax.

It was certainly not a hill worth dying on, to use an expression everyone in uniform understands. Stars and Stripes has fans on both sides of the aisle on Capitol Hill. Republican and Democratic senators wrote a joint letter to Esper last week, urging him to delay the paper’s shutdown until Congress could fully review the Pentagon’s budget proposal. If elected officials think it is worth the public’s money to bring the publication to our far-flung military, the brass has little choice but to go along.

Then there is the president, who is notoriously fussy and fickle in his relationships with media outlets. He probably isn’t a Stars and Stripes reader himself. But he doesn’t need to read it to understand that depriving America’s troops of an independent news channel is a bad idea on its face.

“The United States of America will NOT be cutting funding to @starsandstripes magazine under my watch,” Trump tweeted last Friday. “It will continue to be a wonderful source of information to our Great Military!”

Our military is an all-volunteer organization. The Wall Street Journal reported that Stars and Stripes boasts an estimated 1 million readers daily, many serving in places that lack reliable and accessible internet. Our support for an independent channel of information that speaks specifically to service members’ interests is a sign of our services’ strength and confidence. It also conveys respect for the people we ask to make all sorts of sacrifices on our behalf, from the mundane to the ultimate.

Independent reporting is bound to annoy people in power on occasion. They should feel free to vent their outrage the way Patton did, or maybe in somewhat less salty fashion. Otherwise, the least they can do is put up with it. It is a fair trade for not having to personally deliver, or read, the paper on the most dangerous route in the world.

Posted by Larry M. Elkin, CPA, CFP®

A GI reads the latest issue of Stars and Stripes, Sainte-Marguerite-d'Elle, France, June 16, 1944.

Photo by Wright, courtesy the U.S. National Archives/Signal Corps Archive.

While news outlets everywhere struggle to survive, the one that retired Gen. David Petraeus once called “the hometown newspaper of the U.S. military” faces summary execution by budgetary guillotine.

Fortunately, President Donald Trump seems prepared to issue a last-minute pardon. Or maybe he already has, depending on how much legal force a tweet from the commander-in-chief carries inside the Pentagon.

For reasons that are obvious only to himself, Defense Secretary Mark Esper was intent on shutting down the Stars and Stripes, which has been part of American military life as far back as the Civil War. Many journalists who later became famous launched their careers at the paper. But it rose to national prominence during World War II largely through the work of one man: cartoonist Bill Mauldin.

Sgt. Mauldin told the story of the war through the eyes of Willie and Joe, two GIs who were not exactly in it for the glory. His nationally syndicated cartoon series, “Up Front,” offered a different view of the war than the one the wartime newsreels and feature films presented. Willie and Joe were bone-tired and war-weary, hoping to survive and go home, but not excited about their prospects. They did not encounter sinister SS storm troopers and Gestapo secret police in combat. Instead, the enemy they faced was made up of other grunts, much like themselves. Mauldin did not disparage the war’s cause, but he did not minimize its cost, either.

Gen. George S. Patton was not a fan. As Allied troops pushed eastward from France in the war’s final months, Patton summoned Mauldin to his palatial Luxembourg headquarters for a stern (and, as Mauldin later recalled, frequently profane) dressing down. But other than jawboning, the imperious general could do little to the young enlisted man. By statute then and now, Stars and Stripes operates with editorial independence, even though it receives financial support and crucial distribution and logistical services from the military.

Mauldin’s wartime work won him his first Pulitzer Prize in 1945, when he was 23. Long after the war, his sardonic cartoons offered baby boomers like me a glimpse of our fathers’ military experiences, which many of them preferred not to speak about.

Although most Americans outside the military community rarely encounter it, Stars and Stripes has continued to bring news of interest to service members through all the conflicts and deployments our military has faced to the present day, from Korea to Afghanistan and Iraq. Whether active-duty military or civilian, Stars and Stripes journalists go where the troops go. A 2019 documentary narrated by “60 Minutes” correspondent Steve Kroft – a Stars and Stripes alumnus – was titled “The World’s Most Dangerous Paper Route.”

Maybe Esper, a West Point graduate, was channeling his inner Patton when he sought to defund Stars and Stripes. The military is a command-and-control organization; it is surely grating at times to have a communications arm of the Pentagon that is, in most respects, independent of that chain of command. Considering the pittance that Stars and Stripes costs in the context of our military budget, the stated rationale of budgetary efficiency lacks credibility. The Pentagon’s contribution to the paper’s budget comes to less than $16 million a year. Esper told reporters that the cut would fund “higher-priority issues” in a military whose annual budget is almost $700 billion. A recent Pentagon memo ordering Stars and Stripes to cease publication after Sept. 30, the end of the current federal fiscal year, had the hallmarks of someone grinding an ax.

It was certainly not a hill worth dying on, to use an expression everyone in uniform understands. Stars and Stripes has fans on both sides of the aisle on Capitol Hill. Republican and Democratic senators wrote a joint letter to Esper last week, urging him to delay the paper’s shutdown until Congress could fully review the Pentagon’s budget proposal. If elected officials think it is worth the public’s money to bring the publication to our far-flung military, the brass has little choice but to go along.

Then there is the president, who is notoriously fussy and fickle in his relationships with media outlets. He probably isn’t a Stars and Stripes reader himself. But he doesn’t need to read it to understand that depriving America’s troops of an independent news channel is a bad idea on its face.

“The United States of America will NOT be cutting funding to @starsandstripes magazine under my watch,” Trump tweeted last Friday. “It will continue to be a wonderful source of information to our Great Military!”

Our military is an all-volunteer organization. The Wall Street Journal reported that Stars and Stripes boasts an estimated 1 million readers daily, many serving in places that lack reliable and accessible internet. Our support for an independent channel of information that speaks specifically to service members’ interests is a sign of our services’ strength and confidence. It also conveys respect for the people we ask to make all sorts of sacrifices on our behalf, from the mundane to the ultimate.

Independent reporting is bound to annoy people in power on occasion. They should feel free to vent their outrage the way Patton did, or maybe in somewhat less salty fashion. Otherwise, the least they can do is put up with it. It is a fair trade for not having to personally deliver, or read, the paper on the most dangerous route in the world.

Related posts:

No related posts.