The House Ways and Means Committee launched crucial hearings on the future of Social Security a few weeks ago, with testimony from the head of the Government Accountability Office that the retirement system “does not face an immediate crisis.”

Just as the R.M.S. Titanic did not face an immediate crisis when the S.S. Baltic relayed a warning of “passing icebergs and large quantity of field ice” ahead.

Social Security’s crisis is a lot closer than most Americans realize. The political battle getting underway over the retirement system’s future is likely to be one of the pivotal economic events of the 21st Century.

Unfortunately, the opening salvos fired by each side have only obscured the battlefield. Defenders of the current system deny that a crisis is coming. Proponents of change, chief among them President Bush, tout the introduction of individual (variously labeled “personal” or “private”) Social Security accounts, along with the use stocks and other investment alternatives, as the main path to a solution.

As GAO chief David M. Walker warned the House committee, private accounts alone will not fix Social Security’s underlying problem, which is that its current pay-as-you-go system of raising money is soon going to fall short. He also warned that while Congress can dither because there is plenty of money to pay benefits today, delay makes any future fix more costly and more painful.

Most Americans, quite possibly including most members of Congress, believe real trouble is decades away. The Social Security trustees reported last year that the old age “trust fund” would most likely run dry in 2042. Unless taxes are substantially increased at that time, retirement benefits would need to be immediately cut by 27 percent to match available payroll tax revenues, with further cuts projected in later years. (By the time you read this article the trustees should have released another annual report, which probably will make small adjustments in these projections.)

I believe the crisis point actually is much closer, because the trust fund is an accounting fiction. Almost from Social Security’s inception, the program has paid all its benefits from current tax collections, lending its leftover “trust fund” money to the U.S. Treasury - which promptly spent it.

At the end of 2003 the trust fund held $1.5 trillion in special debt obligations of the U.S. government. By 2013, the trust fund is expected to reach nearly $3.6 trillion, all held in these special Treasury obligations. A $3.6 trillion kitty sounds pretty good. But imagine you had a $3.6 trillion IRA account from which you have already borrowed all the money, leaving an IOU. Now it is time to retire, and you want to withdraw some cash from the IRA. What happens?

Social Security will reach that point sometime around 2018, when annual benefit payments begin to exceed annual collections. At that point the Treasury will need to begin redeeming those special securities if Social Security is to meet its obligations. But where will the Treasury get the cash? At the end of fiscal 2004 the Treasury’s total monetary assets including gold reserves totaled $97 billion, down from $119 billion a year earlier. The operating cash included in those figures was only $31 billion last year, down from $50 billion. Our deficit-burdened Treasury simply does not have anywhere near the kind of cash Social Security will need to tap once retirement payments begin to outstrip tax collections.

Lawmakers seeking an easy way out might want to try some creative financing techniques. Maybe we could sell and lease back the Capitol. Otherwise, the only options to meet Social Security’s obligations are to borrow the money domestically, to borrow from foreigners, to raise taxes, to divert huge amounts of general tax revenues from other current spending, or to simply print more dollars.

|

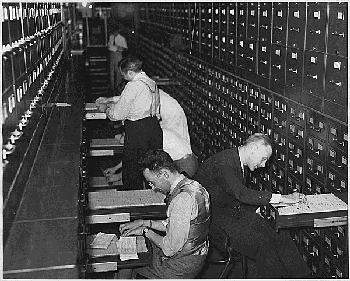

Clerks file workers’ applications for Social Security account numbers. |

All of these approaches have serious drawbacks. Heavy borrowing, either domestically or overseas, will tend to drive up interest rates and reduce economic growth. Overseas borrowing further presumes foreigners are interested in financing our retirement spending; they may be willing to do so only if the dollar’s value is first driven down to a point that they see little risk in taking on additional exposure to the greenback. Raising taxes is going to be painful economically as well as politically. Diverting tax revenues will curtail other government activity. Printing more money would be highly inflationary; to compensate, the Federal Reserve might well push up interest rates anyway, again damaging the economy.

Social Security’s trustees estimate that over the next 75 years, the unfunded gap between the retirement program’s resources and its obligations is $3.7 trillion. Even this figure, however, is an understatement, because the trustees treat today’s $1.5 trillion trust fund balance as a resource, even though it really is not on hand to be spent. The true 75-year funding gap is most likely north of $5 trillion.

Defenders of the status quo argue that with relatively minor changes, Social Security can be preserved in its current form. They can cite, among other sources, a study by the Center for the Economics and Demography of Aging at the University of California - Berkeley, which projects that the currently promised benefits can be paid over the next 75 years by raising the current 12.4 percent payroll tax to 14.4 percent. The study also finds an opportunity to keep the program solvent for a century by a combination of raising the payroll tax one percentage point to 13.4 percent, increasing the retirement age to 69 by 2024, and investing one-quarter of the Social Security trust fund in equities by 2015.

There are some holes in this analysis. First, it treats today’s $1.5 trillion trust fund balance as though it really exists in some form more useful than an unsecured IOU. That is not the case. Second, it ignores the fact that the current pay-as-you-go system is like a game of musical chairs. Because today’s workers are always paying benefits to yesterday’s workers, the system will continually have an unfunded debt to current workers – one that is likely to mushroom over time, as each generation of retirees demands better benefits than the preceding generation. History has shown that Washington is susceptible to those demands, as long as paying the bill can be put off.

President Bush, by endorsing individual accounts that can be invested at least partly in equities, approaches the problem from the opposite direction. He would allow today’s younger workers to begin funding their own retirement, thus finally putting Social Security onto the path of self-sustainability that was part of its original blueprint, but which was almost immediately abandoned [see accompanying story]. By allowing investments in equities, or for that matter in any instrument that involves a real economic return from private sector activity, he would permit the program to create genuine wealth that can be used to sustain future retirees.

There is nothing magical about individual accounts. A large, universal retirement fund can invest in equities just as easily and with lower risk for the individual. This is exactly what happens in virtually every traditional private-sector pension plan in America.

Also, we financial planners often see individuals grossly mismanage their self-directed retirement accounts in IRA and 401(k) programs. A worker who will not need to tap funds for many years may keep most of her money in low-yielding cash because she is irrationally afraid of short-term stock market volatility. Another worker who may need to withdraw funds within a year or two may leave himself much too exposed to a sharp downturn such as we saw at the beginning of this decade. Many workers hold investments, often in their employer’s stock, that are not nearly diversified enough. Any program of individual Social Security accounts would have to try to address these all-too-common mistakes.

By diverting current payroll taxes into individual accounts, the President would accelerate the need for the Treasury to borrow massive amounts of money to meet current benefit payments. However, he is only accelerating, not creating, that need to borrow. If the Treasury continues to gobble up all of the taxes paid by today’s workers to pay benefits to yesterday’s workers, it will ultimately have to borrow the same money (plus interest) to meet future obligations to today’s workers.

Backers of individual accounts would argue that by allowing and requiring each individual to fund a substantial share of his own retirement, we create a fence that prevents Washington from tapping the resulting financial reserves for other purposes whenever it comes under political pressure to do so.

|

| Clerks record and file individual Social Security account information. |

Of course, the most straightforward way to close the gap between available resources and promised benefits is to reduce the benefits. Any solution to Social Security’s woes almost certainly will involve changes to the retirement age, and probably other changes in benefit computations as well. Trying to mitigate deadly opposition from the senior citizens’ lobby, President Bush has proposed to shield anyone now age 55 or older from such changes. This means the bulk of the change would fall on that great bulk of baby boomers born between 1951 and 1964. Workers younger than the boomers have more time to prepare, and for the most part have always understood that Social Security might have very little to offer them once the boomers were done with it.

|

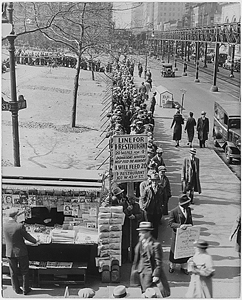

| Long lines of people wait to be fed in New York City in 1932. With private funds, free food was distributed to the unemployed in some urban centers. |

The debate about Social Security’s future is ultimately about what kind of program it should be. In its very earliest conception, Social Security was supposed to be a means for government to help the average citizen fund at least a basic standard of living in old age. It immediately morphed, however, into a program that transferred wealth from one group of citizens (younger and working) to another (older and retired). Congress proved much too willing to meet demands by the older group for a better standard of living, which it never paid for, while promising younger workers that they, too, would be supported by yet another generation of workers and politicians that would follow.

Our nation’s older citizens have what amounts to a union, AARP. AARP is the leading opponent of the president’s Social Security proposals. As it says on its Web site, “Yes, the system needs some adjustments, but we don’t need to destroy Social Security in order to fix it. ”

A good argument can be made that President Bush is merely seeking to return Social Security to the original idea promoted by Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In his message to Congress in January 1935, in which he proposed the Social Security legislation adopted later that year, FDR declared that “the system adopted, except for the money necessary to initiate it, should be self-sustaining in the sense that funds for the payment of insurance benefits should not come from the proceeds of general taxation.”

Social Security is at least $5 trillion short of being able to keep its promises. AARP and other defenders of the current system are essentially arguing that general taxation should meet most or all of that gap. In effect, they argue that once we reach a certain age, society owes us a living.

Social Security’s creators understood that such an attitude could destroy individual incentives for thrift and self-reliance, though soon enough they pushed those concerns to the background and turned Social Security into just such a wealth transfer system.

President Bush serves our children and grandchildren well when he insists that they be able to set aside resources for their own future rather than merely fund the leisure of their baby boomer parents. Individual accounts are not necessarily the only way to reach that goal, though in an era of chronic government budget deficits, they are not a bad way, either.

Regardless whether individual accounts are established, regardless whether Congress finds the will to take action now or chooses to delay, Social Security is either going to undertake a major course correction, or it will soon strike a financial iceberg and sink. If it goes down, there is a very good chance it will take the world’s leading economy to the bottom with it.

Linda Field Elkin contributed research to this report.