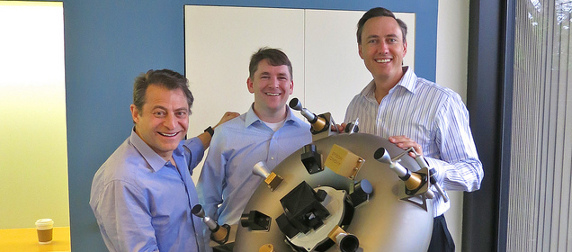

Peter Diamandis (left) and Chris Lewicki (center) of Planetary Resources pose with SpaceX board member Steve Jurvetson and an early build of their company's 3D-printed satellite.

Peter Diamandis (left) and Chris Lewicki (center) of Planetary Resources pose with SpaceX board member Steve Jurvetson and an early build of their company's 3D-printed satellite.

Photo courtesy Steve Jurvetson.Asteroid mining is a science fiction staple, appearing in novels, short stories and films from the 1940s to the present day. New legislation may hint that the practice could make the leap from fiction to reality relatively soon.

The new law is also a useful reminder that private investment and risk-taking are only possible when investors are assured that they will be allowed to enjoy and exploit the fruits of their efforts.

President Obama recently signed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. While the new law contains several provisions, its overall aim is to encourage private companies to proceed with space exploration efforts. The law limits government interference for at least the next eight years and provides for permanent financial incentives, by allowing companies to claim ownership of any nonliving materials they extract or collect in space.

While no company is ready to launch such an endeavor immediately, several could credibly do so soon. SpaceX and Blue Origin have gotten as far as launching rockets into low-Earth orbit, and companies like Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries have already announced their intentions to extract materials, including platinum and other rare Earth minerals, from near-Earth asteroids.

The main challenge to such endeavors is developing methods that make the process cost-effective. Even for very expensive substances like platinum, the costs involved in successfully making contact with an asteroid and then extracting the target materials are very high, especially when factoring in the need for fail-safes and the potential for accidents.

Before the new legislation took effect, companies that sought creative solutions to these problems faced the daunting prospect that their rights to any materials they extracted were unclear.

Under the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, no nation can claim sovereignty over any celestial object, whether an asteroid or the moon. If we ever create a colony on Mars, it cannot become the 51st U.S. state. However, the new law codifies what has long been unofficial U.S. policy: Although celestial bodies themselves are not up for grabs, companies who obtain or extract resources from them have ownership rights to what they take.

While U.S. lawmakers say that the new law does not violate the international treaty, some observers expect resistance from the international community. Henry Hertzfeld, an expert in space law at The George Washington University, told Scientific American that some pushback is more or less guaranteed. “In what form and how strong, and what the timing of how other nations react to this is something I don’t know and can’t predict,” he said. “But not all are going to like it, that I do know for sure.” It seems likely that the law will be, at minimum, a topic of discussion at next year’s meeting of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

It is possible, too, that some nations may use the American law as an excuse for bending or even breaking existing agreements. As Slate observed last year, China has previously hinted at possible mining operations on the moon. This would, at least in theory, be consistent with our own approach - assuming China neither claims sovereignty over lunar territory nor interferes with the operations of other enterprises there. Given China’s shaky respect for boundaries here on Earth, however, there is some reason to be wary, even if there is nothing inherently wrong with the Chinese plans.

In fact, we can contrast the new U.S. law with an existing space-related treaty - one in which we did not participate. The 1979 Moon Agreement, signed by 16 non-spacefaring nations, sought to define space as inherently communal and to require “equitable sharing” of any developed lunar resources. In other words, everyone has inherent rights to benefit from mankind’s achievements, no matter who put in the work, took the risks or footed the bill.

The problem, of course, is that when something is as challenging, risky and expensive as space exploration, you have to leave some incentives in place or no one will bother. Now that the Cold War no longer fuels governments to spend vast sums of money on space, private companies have a clear role to play. But companies, as a rule, want to make a profit on their enterprises.

So the new legislation can serve as a reminder that safeguarding investors is a key ingredient in fostering innovation in the private sector. For that matter, it might serve as a reminder to our own political left that nothing is gained when nothing is ventured, and that respect for property rights is as critical for progress here on Earth as it is beyond our atmosphere.

When it comes to space exploration, property rights remain an academic issue - for now. But a time will come, probably well beyond this baby boomer’s lifetime, when some foreign but terrestrial power will try to appropriate space property that has been developed by others.

Will the Americans of the future protect their interests against space pirates, as the Americans of the late 18th and early 19th centuries resisted British and Barbary Coast incursions? We can’t know, but I hope we and our heirs maintain the physical and moral strength to do so.

Posted by Larry M. Elkin, CPA, CFP®

Peter Diamandis (left) and Chris Lewicki (center) of Planetary Resources pose with SpaceX board member Steve Jurvetson and an early build of their company's 3D-printed satellite.

Photo courtesy Steve Jurvetson.

Asteroid mining is a science fiction staple, appearing in novels, short stories and films from the 1940s to the present day. New legislation may hint that the practice could make the leap from fiction to reality relatively soon.

The new law is also a useful reminder that private investment and risk-taking are only possible when investors are assured that they will be allowed to enjoy and exploit the fruits of their efforts.

President Obama recently signed the Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. While the new law contains several provisions, its overall aim is to encourage private companies to proceed with space exploration efforts. The law limits government interference for at least the next eight years and provides for permanent financial incentives, by allowing companies to claim ownership of any nonliving materials they extract or collect in space.

While no company is ready to launch such an endeavor immediately, several could credibly do so soon. SpaceX and Blue Origin have gotten as far as launching rockets into low-Earth orbit, and companies like Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries have already announced their intentions to extract materials, including platinum and other rare Earth minerals, from near-Earth asteroids.

The main challenge to such endeavors is developing methods that make the process cost-effective. Even for very expensive substances like platinum, the costs involved in successfully making contact with an asteroid and then extracting the target materials are very high, especially when factoring in the need for fail-safes and the potential for accidents.

Before the new legislation took effect, companies that sought creative solutions to these problems faced the daunting prospect that their rights to any materials they extracted were unclear.

Under the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, no nation can claim sovereignty over any celestial object, whether an asteroid or the moon. If we ever create a colony on Mars, it cannot become the 51st U.S. state. However, the new law codifies what has long been unofficial U.S. policy: Although celestial bodies themselves are not up for grabs, companies who obtain or extract resources from them have ownership rights to what they take.

While U.S. lawmakers say that the new law does not violate the international treaty, some observers expect resistance from the international community. Henry Hertzfeld, an expert in space law at The George Washington University, told Scientific American that some pushback is more or less guaranteed. “In what form and how strong, and what the timing of how other nations react to this is something I don’t know and can’t predict,” he said. “But not all are going to like it, that I do know for sure.” It seems likely that the law will be, at minimum, a topic of discussion at next year’s meeting of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

It is possible, too, that some nations may use the American law as an excuse for bending or even breaking existing agreements. As Slate observed last year, China has previously hinted at possible mining operations on the moon. This would, at least in theory, be consistent with our own approach - assuming China neither claims sovereignty over lunar territory nor interferes with the operations of other enterprises there. Given China’s shaky respect for boundaries here on Earth, however, there is some reason to be wary, even if there is nothing inherently wrong with the Chinese plans.

In fact, we can contrast the new U.S. law with an existing space-related treaty - one in which we did not participate. The 1979 Moon Agreement, signed by 16 non-spacefaring nations, sought to define space as inherently communal and to require “equitable sharing” of any developed lunar resources. In other words, everyone has inherent rights to benefit from mankind’s achievements, no matter who put in the work, took the risks or footed the bill.

The problem, of course, is that when something is as challenging, risky and expensive as space exploration, you have to leave some incentives in place or no one will bother. Now that the Cold War no longer fuels governments to spend vast sums of money on space, private companies have a clear role to play. But companies, as a rule, want to make a profit on their enterprises.

So the new legislation can serve as a reminder that safeguarding investors is a key ingredient in fostering innovation in the private sector. For that matter, it might serve as a reminder to our own political left that nothing is gained when nothing is ventured, and that respect for property rights is as critical for progress here on Earth as it is beyond our atmosphere.

When it comes to space exploration, property rights remain an academic issue - for now. But a time will come, probably well beyond this baby boomer’s lifetime, when some foreign but terrestrial power will try to appropriate space property that has been developed by others.

Will the Americans of the future protect their interests against space pirates, as the Americans of the late 18th and early 19th centuries resisted British and Barbary Coast incursions? We can’t know, but I hope we and our heirs maintain the physical and moral strength to do so.

Related posts: