Budgeting is always an exercise in adjusting to changing circumstances. But for Americans under 40, the circumstances have never included significant inflation — until now.

While inflation has cooled somewhat since 2022, it remains higher than it has been in decades. Last year brought the biggest year over year increase in inflation since 1981. Consumer prices rose 9.1% in June 2022 compared to the year prior. In January, prices were up 6.4% compared to the previous year, so inflation has calmed compared to mid-2022. Still, it remains well above the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%.

Consumers have also seen the prices of particular goods and services spike in the past few years. Egg prices rose 70% over the past 12 months in response to an outbreak of avian flu that affected more than 57 million birds, in combination with the effects of increased fuel costs and chicken feed prices. Americans had trouble tracking down cream cheese for the 2021 holiday season after a cyber attack on Schreiber Foods shut down operations for days, amplifying the existing effects of labor shortages and supply chain pressures. In an inflationary environment, these sorts of unforeseen pressures can drive up the prices of specific items in ways that create even more pressure on consumers’ budgets.

Before you get to work on adjusting your financial life to weather the current round of inflation, it is worth taking time to understand how inflation works.

Understanding Inflation

Informally, most people understand that “inflation” means the prices of goods and services are rising. For economists, the measure is usually more specific: a price comparison of a particular basket of goods, services or both over a particular time period (often one year). You may often encounter the consumer price index, sometimes shortened to CPI, in news reports. This measure reflects the change in cost of a collection of commonly purchased items relative to a base year. The items that CPI reflects usually remain consistent from year to year to allow for effective longer-term comparisons, though occasionally they change to reflect widespread shifts in consumer behavior.

However it is measured, inflation means a decrease in consumer buying power. Even if your income doesn’t change in dollars, each dollar you earn can buy less as inflation rises. It is also worth remembering that, while measures such as CPI can give you a sense of the overall state of the economy, prices of different goods and services change at different rates. For example, the prices of traded commodities reflect daily market adjustments, while costs governed by contracts (such as housing) may take longer to reflect inflationary pressures.

The basic principle behind inflation is that demand outpaces supply. But in the real world, when and how this happens can be complex. On the supply side, rises in production costs, including changes in the availability of fuel or raw materials, can be passed on to consumers directly. Or they can simply mean that producers can make fewer products. In recent years, supply shortages have been caused by the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on global trade; the war in Ukraine, which has had an especially pronounced effect on energy and food prices; labor shortages during COVID lockdowns and as a result of the so-called “great resignation”; and fallout from a variety of natural disasters and severe weather events.

Increased demand can have as much effect as constricted supply. Government stimulus can sometimes boost demand, as can large-scale consumer behavior. In 2020 and early 2021, many Americans ended up saving more as they mainly stayed at home during mandated lockdowns. Certain goods became scarce, while other forms of spending dried up entirely. But as life returned to more routine rhythms, pent-up demand returned in many cases. Similarly, as Americans finally use up supplies they may have hoarded a few years ago, regular purchasing rhythms returned for goods ranging from toilet paper to flour to cleaning wipes.

Inflation also has a more ephemeral — but no less important — contributing factor: expectations. If workers expect inflation to continue, they will often demand wage increases to preserve their spending power. This can create a cycle in which the cost of labor rises, and businesses pass on those costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. Such a spiral is not inevitable, but it is not uncommon. It can be a major factor in hyperinflation, though usually in concert with broader societal or governmental dysfunction.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve has taken steps to try to bring inflation back down. We do not yet know how high interest rates will climb before inflation comes down to target levels. In the meantime, however, individuals can take steps to adjust their budgets to reflect increasing prices.

Budgeting Amid Inflation

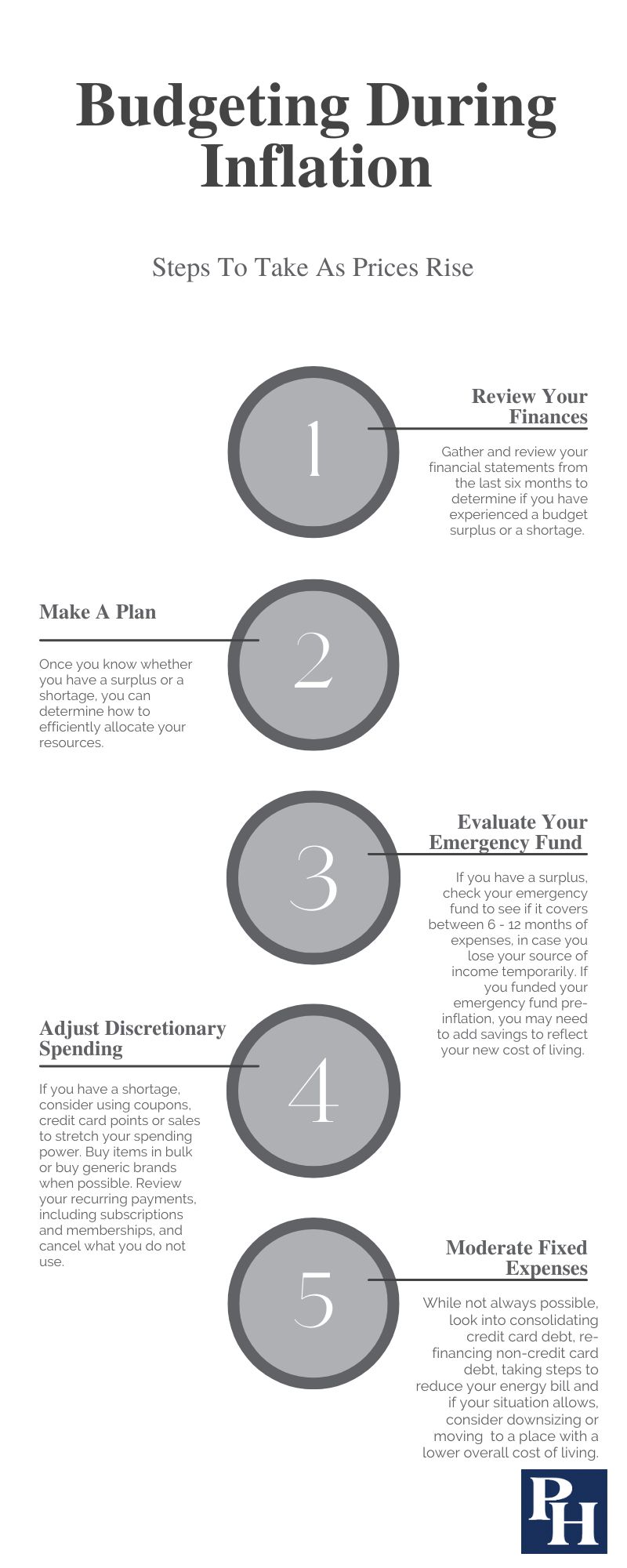

The first step in adjusting your budget is to reevaluate your financial situation. (If the basics of budgeting are new to you, Chapter 3 of our book The High Achiever’s Guide to Wealth provides a full overview.) “Fixed” costs such as housing, transportation or child care may be rising a little, or a lot; if your earning power is not keeping pace, you may need to make adjustments elsewhere.

First, gather your bank and credit card statements for the past six months or so and put together a full picture of your situation. List all your sources of income, using after-tax figures if possible. If the nature of your income makes this difficult, a good rule of thumb is that you can expect to set aside between 15% and 20% for taxes if you live in a state with income tax. Then list your spending. Comparing these numbers, you can determine whether you experienced a surplus or a shortage in the past few months. Using your average expenses and income, you can also estimate whether you expect a surplus or a shortage going forward.

If you have a surplus, consider whether your emergency fund is sufficient to cover your current monthly expenses, or whether you funded it at pre-inflation level. In the latter case, it is good to use your surplus to top up. An emergency fund should cover between 6 and 12 months of expenses, in case you lose your source of income temporarily. If your emergency fund is in good shape, you can save and invest toward other goals. At a minimum, it’s always a good idea to contribute enough to your retirement account to fully secure any employer match.

If your income isn’t keeping up with your expenses, you will need to make adjustments accordingly. How radical these adjustments will be depends on the size of your shortfall and your goals for a surplus. Beyond breaking even, do you need to save for an emergency cushion? If you are saving for long-term goals, how much time do you have to reach them through saving and investing?

Once you know where you currently stand, if you need to make adjustments, the first place to look is your discretionary spending. There are more techniques for reducing nonessential spending than I can cover in this article, but here are a few with wide appeal:

1. Shop smart. If you are looking to trim your budget, some techniques simply take more time and attention. Consider looking for coupons or sales to stretch your spending power. To the extent you can, buy in bulk or buy generic alternatives to brand-name products. Making a list and sticking to it, or even placing an order for curbside pickup, can help you to avoid impulse purchases during shopping trips. And if you have a credit card that offers you rewards, consider using it more often as long as you are in a position to pay it off in full every month. Credit card points can help you to stretch a budget, though if you know you will be tempted to overspend, avoid this technique as it could do more harm than good.

2. Try the envelope method. Some people find it helpful to use cash to regulate discretionary spending. The method works like this: Set an allowance for weekly spending. You can either divide it between categories like dining out, entertainment and nonessential shopping, or leave the spending under a larger umbrella. Regardless, set an allowance for the week and withdraw sufficient cash to cover that amount. Once it’s gone, it’s gone. My household has used this method on occasion, and we always find it eye-opening. It has helped us get back on track with our budgeting and made us more aware of our weekly outflow.

3. Look for places you’re paying for convenience. You may be able to reduce some of your discretionary spending by adjusting your habits. Delivery services like Uber Eats and DoorDash add up quickly not only because of the costs of food, but the additional expenditure on fees and tips. Cooking at home is great, but even just picking up takeout instead of having food delivered can help over time. Similarly, recurring payments can sneak up on you, especially if they are set to autopay. Examine your subscriptions and memberships to see if you’re paying for any services you no longer want or need.

4. Buy used when you can. Many items, including toys, furniture and clothes, are available used, often at a significant discount. Consider whether secondhand goods might fit your needs when you’re adjusting your discretionary spending. In addition to consignment or thrift stores, you may find websites like AptDeco or Poshmark useful options. You may also find secondhand electronics a bargain, especially as many manufacturers now offer certified pre-owned options that can give you peace of mind when it comes to an item’s quality and function.

While discretionary spending is the easiest part of your budget to adjust, it isn’t your only option. You may also look for ways to moderate some of your fixed expenses.

If you carry credit card debt, it may make sense to consolidate to the card with the lowest interest rate as you work to pay it off. Depending on your credit score and the rest of your financial situation, you may find it practical to open a new card that offers a 0% annual percentage rate for some promotional period (often between 6 and 21 months). Moving the balance to this new card can give you a window to pay down existing debt. Before pursuing this option, however, be honest with yourself about how likely you are to pay it off before the new card’s interest kicks in.

Refinancing non-credit card debt may also be worthwhile, but it very much depends on the details. Interest rates are relatively high as the Fed tries to counter inflation, so if your debt has a fixed interest rate from when rates were lower, it probably won’t make sense to refinance. On the other hand, if your credit rating or overall financial situation has substantially improved, refinancing may be to your advantage. Bear in mind that if you have government-issued student loans, refinancing can mean losing some of their benefits, so proceed with caution. Refinancing may also incur bank fees, so the rate adjustment would need to be material.

If you are in debt of any kind, it is important to prioritize paying at least the minimum, even if your budget adjustments mean cutting back on extra payments for cash flow reasons. (For more about balancing debt repayment with budgeting, see my colleague Thomas Walsh’s article “Take Control Of Debt Repayment.”)

You may find other places to reduce essential spending. Consider taking steps to reduce utility bills. These may include updating or servicing heating and cooling systems; switching to energy-efficient appliances and light bulbs when possible; or turning down central heat or air conditioning within reason. You may similarly want to reduce transportation costs by carpooling, consolidating trips when you can, or taking public transit if possible.

As always with budgeting, finding significant adjustments can make a bigger difference than cutting a lot of corners. Forgoing your daily latte can help, but it means less than deferring a major home improvement project or deciding to purchase a used car rather than a new one. Housing is a major component of most Americans’ budget; while it’s not practical for many people, if your circumstances allow it, downsizing or moving to a place with a lower overall cost of living can have a major impact on your overall finances. (If you are considering this approach, however, be sure to factor in the not-insignificant costs of selling your home and of moving.)

Finally, while controlling spending is usually easier than adjusting income, income is not always entirely beyond your control. While it’s not possible for everyone, it is worth at least considering whether changing jobs, adding a second job or starting a side business may help you to adjust to higher prices. Unemployment remains low, which means that in many industries, the market is still favorable to employees hoping to find a job that properly values their skills.

A final note: As inflation rises, it provides a reminder that investing cash you don’t need in the short term is an excellent way to preserve your future buying power. While risk-averse investors may be tempted to keep their nest eggs safely away from the market’s ups and downs, such a strategy is risky in its own right. Long-term investing in a properly diversified portfolio is one of the best ways to make sure inflation does not eat away at your future spending power.

Inflation is not comfortable, but it also isn’t a catastrophe. While no one can say how long this round of inflation will last, consumers who take the time to make adjustments to their budgets are well-positioned to be patient in the meantime.