College professors have long been told that they must publish or perish. The universities that print their books are facing a different ultimatum: stop wasting money on ancillary activities, like publishing, or perish.

While universities around the world operate presses devoted to scholarly work, only the University of Chicago, Oxford and Cambridge University presses are generally believed to be profitable. The rest rely upon their university to fund them through the tuition, endowments, and, in some cases, state subsidies that finance general campus operations.

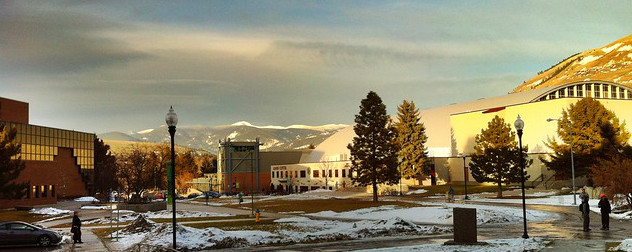

This practice is beginning to fade. Facing rising costs, about half a dozen schools have closed or suspended their presses within the past three years. The University of Missouri is the most recent example of school officials confronting their problematic press. The school’s new president, Timothy M. Wolfe, has announced that the university will no longer continue to shelter its unprofitable publishing arm. The University of Missouri Press now must operate without the $400,000 annual subsidy it previously received. To make ends meet, some paid employees will be replaced with students.

Predictably, professors are horrified. Without amply funded university presses, many fear that the dissemination of knowledge will cease and academia will fall into a Dark Age. Arguing that a university is intended to both educate students and provide faculty an opportunity to engage in important intellectual discourse, college professors claim that this sort of intellectual discourse cannot be sustained by an unsubsidized or commercial publishing house.

I am not arguing that research unsuited to commercial publishing has no value, nor am I arguing that professors should slavishly grade papers into the night without a spare minute to advance their specialized fields of knowledge. I have one simple objection to the current system: It is unconscionable for universities to subsidize their faculty’s publications while students are racking up ever-higher debt to pay skyrocketing tuition.

Professors would likely argue that students benefit indirectly from the money they involuntarily contribute to university presses, with better-informed and better-known faculty to teach them. In reality, however, the professors who spend the most time on research and publishing are often the ones who spend the least time teaching undergraduates. Those undergrads help fund the tenured faculty's research while being taught by graduate assistants and non-tenure-track adjuncts.

Fortunately, there are many ways professors can share their knowledge without financially burdening their students. One way is to rely on private and government grants to finance the publication of scholarly works.

Alternatively, professors might consider making their work more accessible to a larger audience in order to attract commercial publishers. Clear, understandable writing can make even a technical topic interesting to a non-technical reader. And as self-publishing becomes easier, academics themselves could pay for the cost of publishing. They can then recoup their investment if their books sell. At the very least, such self-publication should count for tenure or promotion.

Also, if what truly matters is academic exchange, not nicely printed book jackets with flattering author photos, professors can find cheaper ways to communicate. Progress does not require printed books. Electronic publishing is cheaper, though not always cheap enough. Rice University replaced its traditional press with a digital-only one, but was forced to shutter its virtual doors after four years due to costs that were still too high.

Regardless of how professors publish their work, it should not be done at students’ expense. The University of Missouri administration has wisely taken away its press’s subsidy. That this is such a rare and newsworthy event says a lot about what's wrong with the way American universities are managed.

August 2, 2012 - 5:07 pm

I do not wish to engage this argument, but prefer simply to state some matters of fact. The comment that only 3 U. presses are profitable is simply wrong. I consult extensively to the U. press community and can assert with certainty that many U. presses are profitable. Those that don’t generate a suplus require subsidies in the aggregate of about $32 million. That figure is more than offset by the U. presses that do indeed turn a profit. That’s on sales (for books only) of around $320 million — U. presses, in other words, derive most of their income from the marketplace. Also, the publishers of journals mostly generate an additional surplus on those publications, which have different economics from books. The remark that electronic publishing is cheaper than print is meaningful only if the higher revenue earned from print publications is not taken into account. Let’s have a second round of this piece, but with the right facts this time.

August 2, 2012 - 5:52 pm

There is undoubtedly some truth in what Mr. Elkin says here, especially his claim that “the professors who spend the most time on research and publishing are often the ones who spend the least time teaching undergraduates.” But he makes one very huge assumption that I believe to be false, viz., that tuition dollars are being used to subsidize university presses. I would be interested to know what information Mr. Elkin has that leads him to make this claim. Does he have access to the budgets of universities, especially private ones, that would show how tuition dollars are allocated sufficient to ground his claim? I doubt it.

August 2, 2012 - 10:55 pm

Have you also looked into what the University of Missouri pays for say, landscaping, parking lots, new furniture, signage, public relations offices, and other costs that could be described as “at students’ expense?” A university press, on the other hand, for pretty modest annual support from the parent university, not only publishes specialized books and journals by and for scholars, but creates teaching materials used in classes, publishes books on regional topics and by regional authors, trains students in useful career skills, and prestigiously extends their university’s name around the world. All the university presses I know (and I direct one) do indeed work, along with their authors, to obtain grants and gifts, exploit electronic efficiencies, expand accessibilty and readerships, etc. U of Missouri Press even paid for their building.

August 3, 2012 - 9:27 am

With all due respect sir, you are appallingly uninformed on a subject about which you chose to write so publicly. Next time do some more thorough research….or fire the researchers you do use and get ones who are competent……and then you will sound more like you know what you’re talking about.

August 3, 2012 - 2:45 pm

University Presses have traditionally been responsible for selecting the best work in the fields that they publish. That is, they invest in collaborative processes with faculty for evaluating manuscripts and deciding on which fields to pursue. Commercial publishers will not have an incentive to do this because it is costly and does not necessarily increase market size for any given title. These costs as well as professional, sensitive editing are far more significant than packaging (i.e. book covers and author photos, mentioned above).

There are many new ways to publish, and they definitely need to be explored. However, the variety of digital platforms do not reduce the need for selecting, editing, evaluating. Self-publishing reduces costs by doing away with many of those functions.

I agree that priorities need to be evaluated given the economic climate and student-debt levels in particular. I also agree that a university could make a valid and good decision to shutter its Press. It is better, though, to have that honest conversation rather than to blame people who are doing a good job with the mission that they have been given by their university. Also, there should be some honesty around the issue of skll levels. Students with no experience can not do the same job as an editor who has worked in a field for many years. I know no one at the University of Missouri or the University of Missouri Press, but I’ve read several articles and statements and think the situation should have been handled much better, regardless of what decision was made.

The poor handling of this situation by the University of Missouri’s senior management raises another issue. One place to start looking for wasteful spending might be in the area of administration that has grown and grown over the past few decades. Funding for University Presses has been dramatically reduced over the past two decades whereas funding for administration of various kinds has increased. Reducing the pay of high level administrators, including that of overpaid financial analysts and investment officers, would be a good place to start. I’m sure there’s much more than $400,000 in wasteful spending in those areas at any major university system in the country, including the University of Missouri.

August 3, 2012 - 5:00 pm

Let me suggest an alternative view of the closure of MU Press.

The increasing costs of higher education are due less to the rising costs of instruction and more to burgeoning university administrations. The corporate management model prevails.

University presses were never intended to be profit centers for their institutions. They were established to disseminate original research, primarily in the humanities and social sciences, as a service to scholarship and the academy. With varying degrees of support from their parent institutions, they do this efficiently and effectively, recovering the majority of their expenses through sales. If there is a fatal flaw in this arrangement it is that while there are hundreds of universities in the United States, only about a hundred have presses. The many are getting a free ride from the few.

Have students and their parents been asked whether they are willing to support their university press? It’s a good value. Fall 2011 undergraduate enrollment at the University of Missouri was 26,000. Assuming for a moment that the $400,000 MU Press subsidy comes only from undergraduate student tuition and fees, the individual student share comes to about $15 annually. But income from MU student tuition and fees was less than 18% of the total FY 2012 revenue of $2.6 billion. Assuming the MU Press subsidy is drawn from across all revenue steams, the individual undergraduate student share comes to $2.77 per year. What does a coffee at Starbucks cost these days?

University presses do not “print” books; they publish them. This consists of a catalog of professional activities including acquisition, development, peer review, copyediting, proofreading, indexing, design, composition, marketing, sales, and distribution—both print and digital. Replacing experienced publishers with students is not a good trade. It is no trade at all.

Supplanting professional publishers with self publishing supported by grants is a chimera. In the main university presses that publish scholarly books publish in the humanities and social sciences. Grants for research and writing are legion; for publishing they are few. And both public and private grant makers require submissions from bona fide publishers, not individual scholars wishing to self publish.

The emperor has no clothes: Digital publishing is not cheaper. In high quality academic publishing, all of the aforementioned expenses persist regardless of the distribution model. The fixed costs of e-distribution, even if it replaces rather than augments print distribution, are virtually the same as print, yet the market requires e-book pricing at a fraction of the print price, thus lowering revenues. The publishing costs of the digital-only Rice University Press weren’t “too high.” They were simply a reflection of what it actually costs to publish quality scholarship.

“Clear, understandable writing” does not happen by accident. It is the offspring of the union between a knowledgeable author and a skilled editor. Yes, books on technical topics written by experts for the lay reader are a marvel. Like Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point or Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, they occasionally even sell well. But scholarship is not advanced by such books. It is rather interpreted for the uninitiated.

August 6, 2012 - 10:46 am

Unfortunately this article is an example of the naivete of financial people who make decisions based on only the bottom line. Unless universities drop the requirement that professors publish books in order to get tenure, an outlet for that publishing must continue to exist. These books are not the books of mass market publishers. The books that are published by university presses go through rigorous review by experts in the specific area of knowledge before they are even accepted for publication. Any idiot can self publish, which thus provides no credibilty as to the quality of the thesis and research. No university would ever consider a self-published book as meeting the requirement for granting tenure, which is based on quality, not quantity.

It seems that increasingly the trend is to devalue the quality of education over the cost of the bottom line. This is not a good model for providing an education that is worth the rising cost of tuition.